I’ve taken a year break from Substack because I’ve been studying for my Master’s in Theopoetics and Writing at a divinity school. Theopoetics leans away from logical explanations of God informed by institutional religion and invites each person to find the divine through poetic articulation of their lived experience.

Long before I started my master's, I started Body Buildings to explore how the design of the built environment allows us to experience the divine. By experiencing the divine, I mean that feeling where things feel just right for a moment, when you feel full, not seeking, when you feel at peace. It is a non-denominational entity; an unseen order that sends us signs, is in the stars or the beauty of nature, the feeling of connection with a lover, or laughter with a friend.

Experiencing architecture is a form of theopoetics - through our senses, we are open and aware of how our body becomes affected, which can result in resonances, or feelings of connection with divinity. As we move through the built environment, we have the capacity to build our understandings of what the divine means to each of us.

Typically, theopoetics is expressed through literature, poetry, and song. It is a communication of theological understanding by the author that also projects a sense of spirit to the reader. Like linguistic art forms, architecture also is a medium, a multisensory experiential process - not a static form, but one that is continuously and endlessly experienced.

Experiencing Architecture

Juhani Pallasmaa is an architect and professor from Finland who has written extensively about the importance of full sensory engagement in a built environment. He argues that there is a tendency towards ocular preference - perhaps in a cultural desire for clarity and control, we’ve shaped modern spaces that don’t resonate with our sensing bodies, and instead push us into detachment and exteriority.1 Examples of ocularcentric architecture include modernist designs like airports, hospitals, or even big box stores - these technologically advanced spaces prioritize white or grey tones, repeated design without nuance, and a lack of tactility, resulting in flat, ageless, sharp-edged spaces that become immaterial and unreal to their users. Upon first imagining, these spaces are clean, composed, and largely uncluttered - but they are difficult to connect with, having few design elements to inspire nostalgic memory.

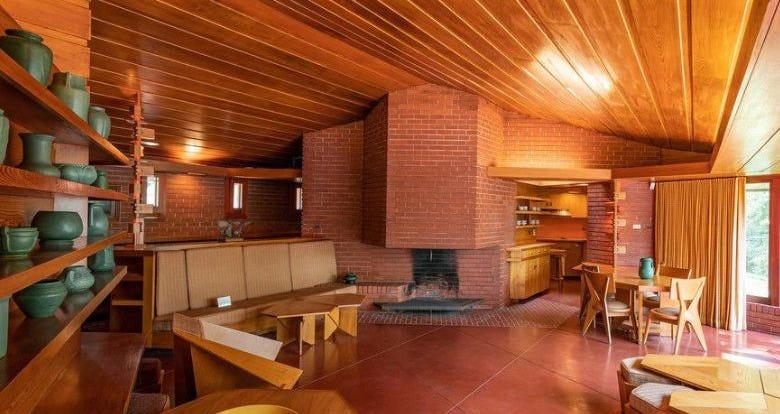

Buildings composed of natural materials like stone, brick, or wood allow the user to be convinced of the veracity of matter, in that they exist outside of this space, and express their age and biological origins. Plastic, glass, and enameled metals present no material essence, no sense of aging. Good design, Pallasmaa argues, should help us experience our temporality.2 Therefore, an architecture that inspires theopoetics might be a well-loved home built of wood or stone, an old church with fading brick walls, or a city of varying dimensions, textures, and colors.

A further example of modern architecture neglecting the body and the senses is the modernist public housing push of the mid-20th century. After World War II, the government sought designs for quick-solution superblocks to house as many low-income people as possible. Two iconic examples would be Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and Cabrini Green in Chicago. The Pruitt-Igoe structures, designed by Minoru Yamasaki, were created as 33 eleven-story buildings with long, narrow hallways, no communal gathering spaces, and long strips of grassy voids between the towering buildings, as landscaping was cut out of the final design. The number of units was prioritized over space within each, so family living space was minimal, kitchen appliances were smaller than average, and building systems were constantly malfunctioning.3

In 1972, Pruitt-Igoe was explosively destroyed, and similar projects, like Cabrini Green in 1995, followed suit. By prioritizing profit and visual organization, the designer with the public housing agency sought to control the issue of housing and poverty into something that could be tucked into neatly designed high rises. This sterile, ocular-focused architecture detaches the user from an “incarnate relation with the environment” by suppressing the body’s senses. These buildings neglected to include elements like green landscaping, comfortable living spaces, natural light, and beauty, thus ignoring resident sensory needs and becoming isolating and uninhabitable. It’s almost as if these buildings were deliberately built with dysregulation of their users in mind.

Nowadays, the narrative has shifted, and designers are privy to the importance of natural beauty in living spaces. Notions like biophilic design are now a massive trend in architectural and interior design, intending to connect people with nature within the built environment: corporations include branded green walls, add water features, and provide access to outdoor space. Biophilic design benefits mental and physical health, as our bodies are “biologically encoded to associate with natural features and processes.”4 The design “engenders an emotional attachment to particular spaces” and “fosters connections between people and their environment.”5 I’d argue this sense of wellbeing extends beyond the mental and physical realm, landing most deeply in human spiritual wellbeing, allowing us to feel a part of an interconnected whole.

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the first popular architects to think about the building in the context of its environment. Materials were often sourced from the site, and the buildings blended into their environment instead of sitting atop it. As a counterpoint to the examples of Pruitt-Igoe or Cabrini Green being harsh and disregulating, Wright envisioned affordable housing with open floor plans, low-pitched roofs, and seamless integration with the environment. Granted, these Usonian homes were marketed towards the suburban middle class, where there was space for single-family homes as opposed to high-density living, but the design nonetheless used affordable materials and simple design features to bring a sense of harmony and beauty into all homes through simple design tactics.

Wright played with shapes, volumes, and textures in all his building designs. One method of this is through what he called “compression and release” - the entrances of many homes would be small, low-ceilinged and dark, then open into a tall-ceilinged, light-filled space. This stark transition creates a greater sense of release and openness when entering the larger living room. This approach and other intentional, organic measures contribute to an overall design that is not a simple “collection of isolated visual pictures, but in its fully embodied material, existential and spiritual presence.”6 This architecture generates a muscular and haptic experience - a spatial encounter, in the flesh.

Architecture as a Medium

In the way religion may help people feel at ease with the existential eternality of life post-death, architecture can help us sequentially experience and navigate our physical world. Gaston Bachelard wrote that architecture can be understood as an instrument “to confront the cosmos.”7 It helps us to make sense of the enormity of all things, in a human-scale size, attentive to our own bodily needs. Pallassma writes, “buildings and towns enable us to structure, understand, and remember the shapeless flow of reality and ultimately, to recognize and remember who we are.”8 It is a physical shaping of an imagined state, the physical output of ideal life. He says, “The task of art and architecture in general is to reconstruct the experience of an undifferentiated interior world, in which we are not mere spectators, but to which we inseparably belong. In artistic works, existential understanding arises from our very first encounter with the world and our being in the world - it is not conceptualized or intellectualized.”9 Architecture is the human language of embodiment. This kind of understanding doesn’t come through thinking, but through feeling and presence. Poetics cannot be reduced to analysis; it must be felt. It is a sensuous cognition.

We are sentient beings and are made to engage the world with all our senses in complex and coordinated ways. Beyond body-mind, this fully integrated system can be described as embodied consciousness. “Our engagement with the world can be understood as a symphony of choreographed senses - a holistic system of being…[that is] primed to deeply engage with the world.”10 Moving through the built environment with embodied consciousness brings the building user into the present moment and makes design come to life.

Experiencing architecture through bodily perception also allows us to open ourselves to new experiences and connections. We are not closed, buffered selves but expansive, interconnected beings. And architecture, as the extension of nature into a man-made realm, provides “the ground for perception and the horizon of experiencing and understanding the world.”11 When we are in these open states, we are more likely to be present not only in our immediate environment but also in that which lies beyond it.

Rilke once wrote that architecture can form “Weltinnenraum” - or “world-inner-space” - a totality of our inner life with outer life achieved through a permeability of the self, an openness to being shaped by space.12 Architecture doesn’t need to be labeled as a sacred space to evoke this feeling; rather, it can be sacred because it evokes a return to self and presence. It suggests that the divine does not need to be discovered “out there” but is incarnate all around us, in our environments and ourselves.

Lived Expression of Architecture

Architecture, like poetics, resides within the interplay of creation and reception. A building’s meaning is generated by the interactive relation that subsumes both the building and the beholder. We do not just occupy built spaces, we participate in their ongoing theopoetic expression. Our felt experience continually unfolds, so we commune by simply being present. An awareness of this interplay requires attention. “Attentiveness, said Malebranche, is the natural prayer of the soul. Poetry is a form of attention, a literal coming to our senses, a turning aside from convention and memory.”13 Resonance refers to a certain quality of human relationships with the world. It is a sensation that occurs without warning, requiring an openness to the unexpected via awareness.

In this way, architecture becomes a medium through which the divine is continuously realized, and theopoetics becomes the awareness towards and expression of moments of resonance - a feeling of connection with the sacred in our daily lives.

Built space, which in itself is a human social product, functions as a partner in doing theology. Architects, artists, planners, and designers should be regarded on a par with theologians who are trained in verbal hermeneutics. Artifacts and built spaces can be approached directly by our intuition, feeling, and thinking.”14

The built environment becomes an active collaborator in theological work, so the architect must consider how the space will be interpreted and experienced by the building’s users and the type of feelings that might be evoked. However, as Mark Oakley reminds us, “a poem’s ultimate meaning is found not in the words but in us, in our response to the words.”15 Architecture and divinity cannot be approached merely from an intellectual capacity; it must be felt and intuited. This is an invitation to trust the body as the communicating vessel with the built environment.

Through careful attention, we can all better notice the sacred communication of the architecture around us. What is the built environment expressing? How does it make you feel?

So yes, this essay, I hope, is a re-introduction to Body Buildings - an ongoing exploration of how we can live embodied and explore the ethical and aesthetic implications of how we reside within space. I wanted to share this essay (which I wrote for my theopoetics class) to give you a sense of where I have been, and where I will be going with this Substack - architecture as theopoetics, seeking meaning in the everyday, divinity emergent in life as we live it.

More to come…!

"Poetics cannot be reduced to analysis; it must be felt. " love

Loved this Nora